Director: Carlos Saura

Screenplay: Rafael Azcona, based on a story by Carlos Saura and Elías Querjeta

Cast: José Luis López Vázquez, Lina Canalejas, Fernando Delgado, Lola Cardona, María Clara Fernández de Loayza, Josefina Díaz, Encarna Paso, Pedro Sempson, Julieta Serrano.

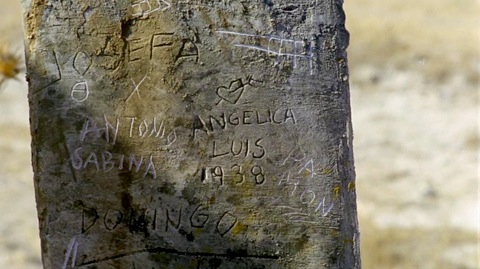

Synopsis: 1973. Luis Cano (López Vázquez) travels from Barcelona to fulfil his late mother's wishes to have her remains interred in the family crypt in Segovia. The trip brings him face to face with the family members he stayed with during the Civil War and leads him to confront the memories and ghosts of his childhood.

La prima Angélica is another of Saura's films that centres on the issue of memory and shares with El jardín de las delicias not only a lead actor (José Luis López Vázquez) but also the use of him to portray a character in both adulthood and childhood. We first see Luis-as-child when Luis-as-adult pulls his car to the side of the road as he sees Segovia in the distance and he becomes lost in the memory of the first time he was at this roadside - his father's car pulls up behind him and his mother (dressed in 1930s attire) comforts Luis and tries to reassure him about his stay with her side of the family (on the right, politically) in a safer area while his parents return to Barcelona. As the Civil War develops, Barcelona becomes cut off, and Luis will see out the war apart from his parents and in the midst of a family from the 'victorious' side. His return to Segovia as an adult in his 40s shows how those war years shaped the person he became and why he now feels the need to confront the past. D'Lugo observes that the film stands as 'the first compassionate view of the vanquished' (1991: 116):

'In choosing the theme of interdicted history -the Civil War years as remembered by the child of Republican parents- Saura pursues more than just the external demons of censorship that had suppressed all but the triumphalist readings of the war. He confronts the psychological and ethical traumas that the official distortions of the history of the war years in public discourse had conveniently ignored but that had scarred and even paralysed a generation of Spaniards' (1991: 115-116).Quintana points out that in the context of Spain today, and the contentious issue of 'historical memory', 'Luis's character gains symbolic force as the first fictional character that recovers the power of memory as an act of resurrection of the hidden and of justice to that which is silenced' (2008: 95). La prima Angélica was controversial and had its release curtailed (one Barcelona cinema that screened it was firebombed), but also became the most commercially-successful film of Saura's career at that point (Quintana 2008: 87).

As with El jardín de las delicias the past is not simply evoked, but reenacted. Although it is perhaps more accurate to say that it is being 'relived', as these are not the theatrical stagings of the earlier film but rather Luis weaving in and out of the present and the past as the return to the family apartment envelops him in memories. Another conceit that is repeated from earlier Saura films is to have the same actors playing more than one character: Lina Canalejas plays Angélica's mother in the 1930s segments and the grown-up Angélica in the present; María Clara Fernández de Loayza plays Angélica in the 1930s and the grown-up Angélica's daughter (also called Angélica) in the present; Fernando Delgado plays both Angélica's father and later her husband (although this is one of the points where the tricks that memory can play on you are pointed out - the grown-up Angélica shows Luis a photo of her father to prove that there is no resemblance to her husband). This 'doubling' obviously aids the transition back and forth in Luis's memory onscreen, which occasionally becomes confusing as Luis loses himself in the past and the lines between the two eras become indistinct. López Vázquez is the only actor to play the same character in both eras - Luis's childhood self is distinguished by voice, body language, and facial expression: for example, his habit of tucking his chin down so that he is looking up (his eyes wide) serves not only to indicate the shy and withdrawn nature of the boy, but also to make the actor seem physically smaller. One particular sequence that I liked comes almost halfway into the film, at the point when Luis has carried out his mother's wishes and is driving back to Barcelona. He stops at the same roadside and the same memory that we saw at the start of the film plays out again. But this time, instead of being immersed in the memory, reliving it, he observes it from the other side of the road; in revisiting the sites of childhood trauma, he has acquired some of the distance required to review the past objectively. He turns his car around and heads back to Segovia to confront the past head on.

References:

D'Lugo, M. (1991) - The Films of Carlos Saura: The Practice of Seeing, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Quintana, À. (2008) - 'A Poetics of Splitting: Memory and Identity in La prima Angélica (Carlos Saura, 1974)', in Burning Darkness: A Half Century of Spanish Cinema, edited by J.R. Resina, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, pp.83-96.