|

| Tim Roth and Kristyan Ferrer |

A tense and suspenseful road movie - and effectively a two-hander for much of its running time - Gabriel Ripstein's directorial debut seems to me to have a good chance of acquiring at least a limited release in the UK, not least because of the presence of Tim Roth and the bilingual nature of a story that unfolds on both sides of the US / Mexican border.

Roth plays Hank Harris, an ATF agent who gets taken hostage and taken over the border into the badlands of Mexico when he attempts to bust two young gun runners (Kristyan Ferrer and Harrison Thomas) who are aiming for the big time. It's revealing that this central scenario is born out of a combination of lack of planning (Harris spots the two men by chance while he's doing his rounds of the gun shows in the area and mistakenly thinks he sees an opportunity when they part company) and panic (Carson (Thomas) acts impulsively towards the threat but it is the unsteady Arnulfo (Ferrer) who then decides to bundle the agent into his truck and drive back across the border alone) - throughout the film, all of the characters are required to think on their feet when events do not turn out as planned and they must try not to let fear get the better of them.

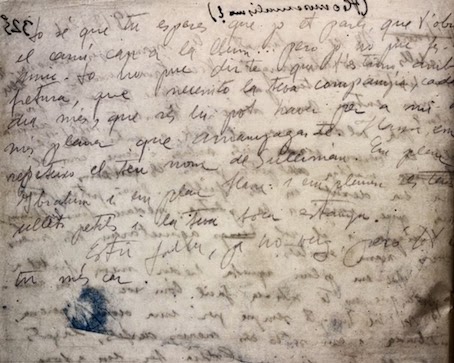

I actually don't want to say too much about 600 Millas / 600 Miles before more people get the chance to see it. I've read some reviews since I saw the film in Edinburgh and a lot of them reveal too much information given the suspenseful nature of the narrative - I'd advise you to go in as blind as possible because I think my experience of it was all the more effective for knowing only the one line synopsis. But the other reason that I'm not going to say too much is that I was so engrossed in the film that I barely wrote anything down (and what I did write down, I wrote over the top of what I'd already written because I was looking at the screen)...which I guess is indicative of a recommendation, but it's not exactly helpful for analysis.

But I will say that it's an interesting representation of the performative nature of masculinities - learning to put up a front, living up to familial expectations, the play and display of homosocial bonding, and knowing that certain situations require different modes of behaviour - particularly in the performances of Ferrer and Thomas whose youth underlines the malleability of the personalities of their respective characters (they are still defining themselves but are also (self)conscious of how they are seen through the eyes of others). But Roth astutely also demonstrates that less is more in his interpretation of an inherently watchful and shrewd man. Ripstein and co-writer Issa López expertly crank up the tension through the skilful use of extended silence and (an often related) lack of comprehension, in a range of contexts - shock at violent events, fear, the sense of being out of your depth, and also not understanding what is being said because it's not your language. The bilingual aspect is also used to indicate shifts in the balance of power onscreen.

In short, I'd like to watch it again because I think it's a really tightly constructed film that pays attention to - and economically employs - the mechanisms of cinematic suspense but is also rooted in its characters and their relationships in a way that we don't see often enough onscreen. I recommend it if it plays near you.