|

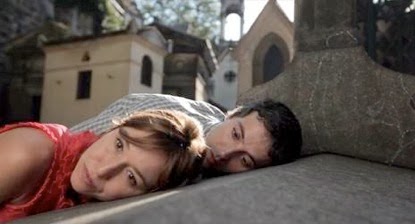

| El futuro |

The 20th edition of the Bradford

International Film Festival ran between the 27th March and 6th April 2014

at the National Media Museum with a diverse programme of films from around the

world, including retrospectives of James Benning, Brian Cox, and Sally Potter,

and Close-Up sections on producer/distributor Charles Urban, and the crime

films of Yoshitarõ Nomura. I managed to catch a bit of (almost) everything but

had timed my visit specifically to see the three Spanish films playing at the

festival: Un ramo de cactus / A Bouquet

of Cactus (Pablo Llorca, 2013), El

futuro / The Future (Luis López Carrasco, 2013), and Costa da Morte / Coast of Death (Lois Patiño, 2013).

You can read the rest of my report on the 'other' Spanish cinema that screened in Bradford over at Mediático.

I am intending to write about all three films here as well, probably starting with Luis López Carrasco's film (it's 67 minutes long, but I only scratched the surface in that report) at some point in the next couple of weeks.