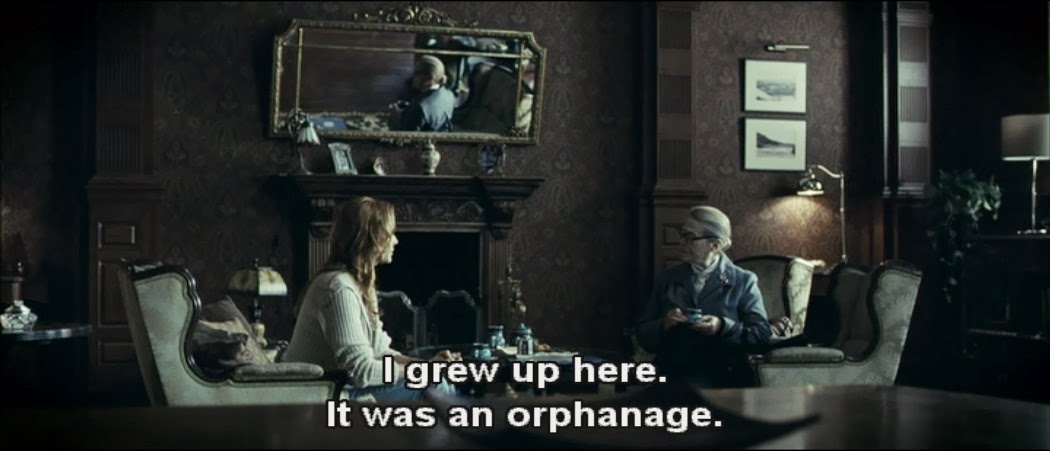

The liminal state in a rite of passage is often marked by physical isolation, even invisibility, in relation to society. This element of isolation and invisibility from society is perhaps most expressed in the Australian Aboriginal ritual of the walkabout, a journey through the wilderness undertaken by a male adolescent. The walkabout can last up to half a year, after which the adolescent returns to society as a changed person. The element of isolation and invisibility in The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage manifests itself in both films through a singular setting: an orphanage, in the middle of the countryside and by the seaside, respectively (Figures 5-6).

|

| Figure 5 |

|

| Figure 6 |

In The Devil’s Backbone, after Carlos is left at the orphanage with no explanation, his entry into its world involves multiple initiation rites that thrust him (and his new friends) into premature adulthood. During his first night at the orphanage, his brief encounters with Santi’s ghost and his entry down in the cellar where Santi’s ghost mainly resides act as initiation rites to be accepted by the other boys. Later in the film, his place among the boys fully accepted and the hidden past of Santi’s death revealed by one of them, Jaime (Íñigo Garces), together they transform the cellar into a place of collective struggle against the fascistic Jacinto. In The Orphanage, in his own way Simón also undergoes a rite of passage. In fact, his rite of passage is a lot more accelerated than Carlos. Through the ghosts of Tomás and of Laura’s childhood friends (who are never seen on screen), Simón learns very quickly of his adopted status and his mortality, secrets that Laura and her husband were keeping from him.

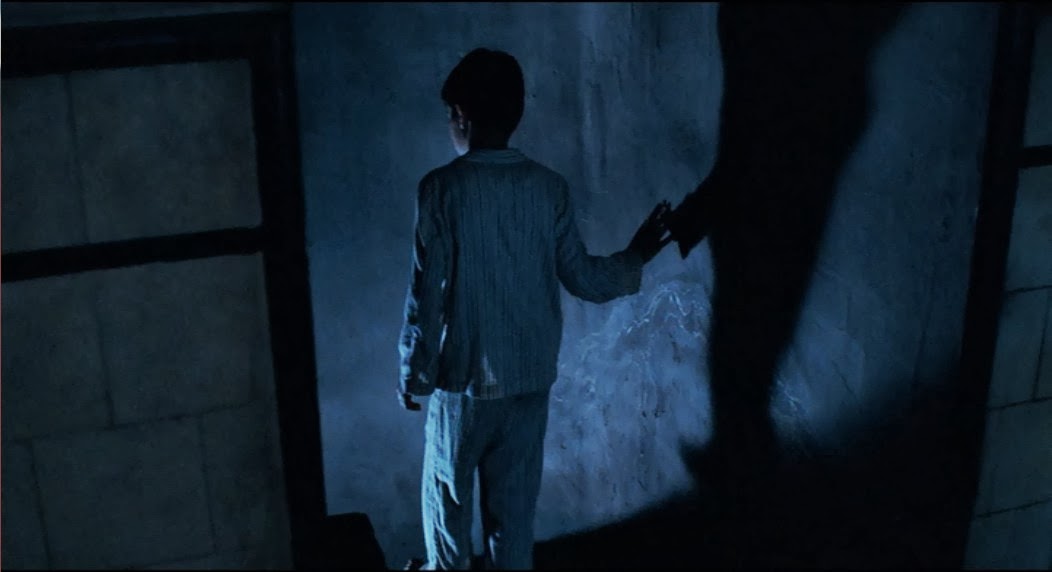

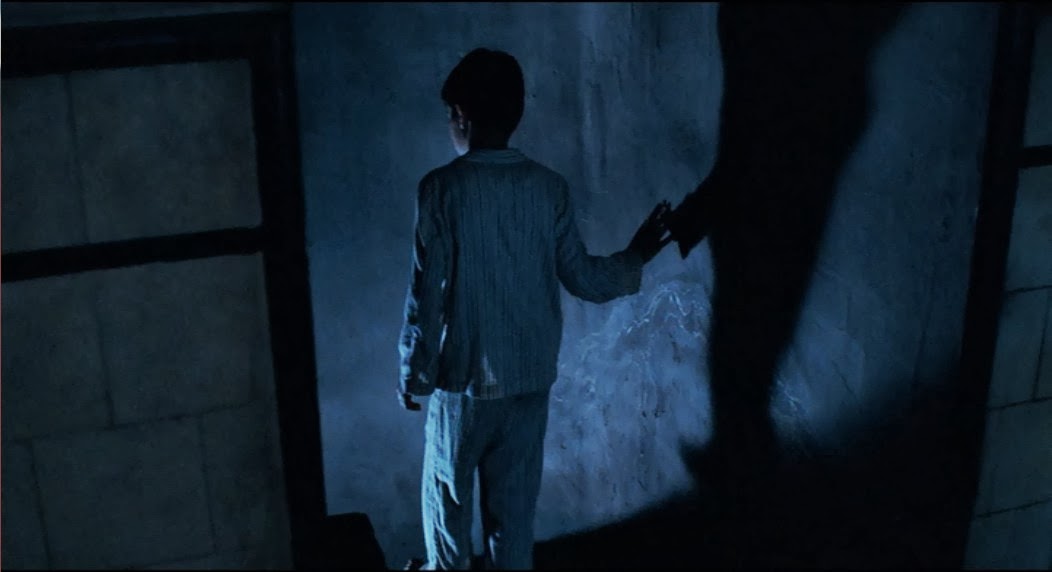

Significantly, the singular setting in both films is also a mark of gothic fiction, as the container of a secret, sometimes a treasure, and the site of violence and traumatic past that gives birth to the secret and the narrative drive to unearth it. More specifically, in gothic fiction, underground structures such as cellars, catacombs, caves, and the like have particular resonance. Architecturally and spatially, these underground structures bring together the plot points of secrets, treasure(s), unknown traumatic pasts, and even ghosts. Both The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage are marked not only by their sole isolated settings, but also variations of subterranean spaces. In The Devil’s Backbone, it is the cooking area with a hearth, which is not only where the safe storing the gold is hidden but also the entryway to the cavernous cellar where Santi’s ghost dwells (Figures 7-8). This cavernous cellar was, in fact, the site of Santi’s death. In The Orphanage, it is the house’s outdoor shed where Laura sees the one who killed her childhood friends at the orphanage without knowing it early in the film. But it is also the cave by the seaside where Simón first meets the ghost of Tomás, whom Laura gradually learns was a deformed boy whose mother Benigna (Montserrat Carulla) worked at the orphanage and had hidden him from her colleagues (Figures 9-11). While playing with Laura’s friends, who were hounding him to take off the paper bag that served as his mask, Tomás died. Lastly, it is also the house’s basement, whose secret entryway is a door inside a closet and where Laura eventually finds not only her son but also Tomás’ past (Figures 12-13).

|

| Figure 7 |

|

| Figure 8 |

|

| Figure 9 |

|

| Figure 10 |

|

| Figure 11 |

|

| Figure 12 |

|

| Figure 13 |

Tempering both of these films’ gothic fiction elements is their fairy tale aspect. Children at the center of the narratives constitutes but one manifestation of this fairy tale aspect. Related to children protagonists is the thematic of abandonment, encapsulated by the very purpose of an orphanage, where Carlos ends up in The Devil’s Backbone and where Laura and Simón remain, despite their adopted family ties. The singular, far-flung setting of the orphanage in both films echoes this theme of abandonment. Another manifestation of the fairy tale aspect comes in the form of objects. In particular, keys in both a literal and figurative sense of enabling the crossing of thresholds are prominent in the two films (Figures 14-17). The notion of crossing thresholds links back to the liminality of these microcosms, between past and present, ghost and human, child and adult, play and violence. Thus, keys denote not just keys or door knobs to open doors or safes but also old photographs to access the past. In The Devil’s Backbone, connecting these literal and figurative keys is Jacinto. He surreptitiously steals the keys from Carmen (Marisa Paredes), the orphanage’s head administrator and teacher, one at a time to find the one that would unlock the safe containing the gold. He also has the keys to the cooking area whose cellar is the site of Santi’s death. And towards the film’s conclusion, he discovers the old photographs of himself as a baby and boy, with his parents, constituting a rare moment of introspection on his part. This moment is a pause in his role as the fairy tale ogre who towers above the children and menaces them because he knows no other way to express himself. At the end of the film in his final confrontation with Carlos and the other boys, the film compares him to the extinct woolly mammoth, about which the boys learn in a lesson with Carmen in the middle of the film. In The Orphanage, connecting the literal and figurative keys is Simón. Following his encounter with the ghost of Tomás in the cave, he performs a very fairy tale-esque gesture of leaving a trail of shells from the cave to his house for Tomás to follow; in this way, the shells serve as a variation of a key to access a space (Figures 18-19). Subsequently, a game of pursuing object-related clues (or keys) begins at the house, which leads Simón to unlock literally and figuratively the knowledge of his adoption and illness. When he disappears, he becomes a kind of key himself for Laura to access the secret past involving Tomás, his death, and those of Laura’s friends at the orphanage.

|

| Figure 14 |

|

| Figure 15 |

|

| Figure 16 |

|

| Figure 17 |

|

| Figure 18 |

|

| Figure 19 |

Definitions of a Ghost

As mentioned earlier, more than anything, the child ghosts in The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage reflect back, or recall, to the world of the living the actual horror that lies in humans, as opposed to serving as mere scare or shock tactics. We return to the thematic realm of the liminal and the ritual, of childhood and adulthood, ghosts and bodies, play and violence. Santi’s ghost in The Devil’s Backbone and the ghosts of Tomás and Laura’s childhood friends in The Orphanage are products of human actions instead of something fantastical. At the same time, these films are careful to avoid demonising the human element that ends up being much more horrific than the ghosts: Jacinto and to a lesser extent Jaime in The Devil’s Backbone and Tomás’ mother Benigna and to a lesser extent Laura’s childhood friends.

Through the vehicle of ghosts, these two films enact encounters with the traumatic, the horrific, the flawed, and the unknown, in other words, for Carlos in The Devil’s Backbone and Laura in The Orphanage. These encounters with the more melancholy and unsettling, darker, and uglier facets of life constitute rites of passage in their own way. When initially confronted by the notion of ghosts, both Carlos and Laura recoil from or deny them, based on their seeming incomprehensibility. In doing so, they recoil from or deny the actual pasts, marginalised and hidden, to which they refer. Yet in the course of the films, both Carlos and Laura, among others, learn to face what they do not know or understand. This process of facing the incomprehensible and therefore fearful is made literal with the ghosts in both films. Taken further, in the context of the ritualistic, liminal, and confrontational, The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage’s encounters with ghosts chart the process of not only facing the incomprehensible and fearful but also realising one’s connection to it, on a humanistic level.

Both films ponder definitions of the ghost: The Devil’s Backbone in its prologue and The Orphanage midway through the narrative. Both films ask, plainly, ‘What is a ghost?’ In so doing and through their definitions, they emphasise the characters’ encounters with the ghosts as something beyond the function of scaring audiences and towards something like ethical action and responsibility, in keeping with the idea of one’s connection to the incomprehensible and fearful, on a humanistic level:

The Devil’s Backbone: ‘A tragedy doomed to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain, perhaps. Something dead which still seems to be alive. An emotion, suspended in time. Like a blurred photograph.’

The Orphanage: ‘When something terrible happens, sometimes it leaves a trace, a wound that acts as a knot between two time lines. It’s like an echo repeated over and over, waiting to be heard. Like a scar or a pinch that begs for a caress to relieve it.'

Each film’s definition of a ghost shares characteristics with the other: repetition; something between living and dead, or past and present; and a physical pain with an indexical counterpart that is not always seen but asking to be acknowledged. In their philosophical definitions of a ghost, these two films locate themselves in a nearly Levinasian realm of face-to-face encounter, echoed literally by Carlos’ meeting Santi’s ghost in The Devil’s Backbone (Figures 20-22) and more figuratively by Laura playing along with the ghosts of Tomás and her childhood friends (Figure 23).

|

| Figure 20 |

|

| Figure 21 |

|

| Figure 22 |

|

| Figure 23 |

In his 1984 essay ‘Ethics as First Philosophy,’ Levinas writes,

‘A responsibility that goes beyond what I may or may not have done to

the Other or whatever acts I may or may not have committed, as if I were devoted

to the other man before being devoted to myself. Or more exactly, as if I had to

answer for the other’s death even before being. A guiltless responsibility,

whereby I am none the less open to an accusation of which no alibi, spatial or

temporal, could clear me. It is as if the other established a relationship or a

relationship were established whose whole intensity consists in not presupposing

the idea of community. A responsibility stemming from a time before my

freedom – before my (moi) beginning, before any present. A fraternity existing

in extreme separation. Before, but in what past? Not in the time preceding the

present, in which I might have contracted any commitments’ (83-84, The

Levinas Reader, ed. Seán Hand, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005).

Strikingly, in his audio commentary to the 2013 Criterion DVD of The Devil’s Backbone, del Toro states along similar lines about the gothic romance, which can also apply The Orphanage:

‘It’s the only genre that teaches us to understand the otherness. At its best,

it is probably the most humanistic genre there is, because by being fascinated

by [and] by being sort of in love with the monsters, we are exercising, in the

abstract, the most beautiful form of tolerance: a desire to understand the

other […], as opposed to trying to destroy it and wipe it from the face of the

earth.’

Rowena Santos Aquino is a Lecturer in the Department of Film and Electronic Arts at California State University, Long Beach. You can find her on twitter, @FilmStillLives.