Though their country’s economic plight worsens daily, Spanish filmmakers are beginning to assess and get to grips with a political climate that is, in the final analysis, antagonistic to artistic endeavour. While films ineluctably express the complex, contradictory tensions that characterise the social context in which they are made, the aim and hope is that any historical period finds its artistic match: those works that grasp the matter at hand, embrace the difficulties ahead, and refuse to evade the work to be done. To this end, there were a significant number of Spanish films at the tenth Seville European Film Festival (SEFF) whose general focus and political persuasion spoke of a palpable discontent with regard to the current state of things. Not every film will be politically charged, of course, and so it is to SEFF’s credit that it waded through what I presume to be a large swamp of mediocrity in order to present, by and large, the strong selection it finally offered. These works speak to the present precisely because they convey an understanding – to varying degrees – of how they relate to the unfolding historical moment.

I have written elsewhere – here

and here

– on Lois Patiño’s Costa da Morte, but some further remarks won’t go amiss (I first saw the film in Locarno in August, and again at the Viennale prior to my arrival in Seville). An essay film on the eponymous Galician coastline – named so because of its history of shipwrecks – Patiño’s debut feature frequently surveys its region from afar, zoomed-in so as to flatten its landscapes and thereby deny a more visually harmonious vantage point. There’s something unnatural about such optical choices: as humans, we cannot, after all, get a closer look at an object without telescopic aid or without physically moving to a closer proximity. Consequently, the film enables an unspoken but ongoing commentary on its own function: in denying itself and its audience a postcard-friendly view of the Coast of Death, it suggests a better understanding of these locales might come from a more idiosyncratic view. By flattening the landscape in such a way, Patiño’s film pits a multiplicity of histories against one another, privileging none and including all. Just as every landscape is the sum of its parts, so the present is the sum of its pasts. Note the plural: at no point in history has there been a moment without contradictions – the remnants of a bygone time, the formations of an era to come.

|

| Costa da morte / Coast of Death |

|

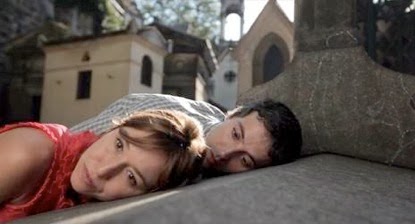

| El Futuro / The Future |

|

| El triste olor de la carne / The Sad Smell of Flesh |

When a recession begins to affect the perfect image of a white middle-class nuclear family, you know you’re in trouble. Alfredo’s burnt-out businessman is a figure of belated if bewildered acceptance, and the only resistance he can summon rings, in the end, all too true. Though some critics might feel its persistent, unbroken take results in unnecessary bouts of dead time – such as when Alfredo is driving, or else travelling on a bus or in a taxi – this is precisely the film’s strength, lingering as it does on those unbearably long passages in which unthinkable stress drains a person’s life away. Indeed, the prospect of financial collapse is now too familiar a prospect for many Spanish people that contrived dramatics are no longer necessary.

Not every Spanish film at SEFF felt like it was making a significant contribution to the battle. Gonzalo García Pelayo’s Alegrías de Cádiz returns its director to filmmaking after three decades in other fields, and feels very much the product of someone lacking practice. (For a serviceably flashy take on García Pelayo’s venture into professional gambling in the 1990s, see Eduard Cortés’s The Pelayos (2012)). Anyone familiar with the director’s work – pseudo-cerebral, flesh-heavy forays into the beauty of women, the joys of sex, monogamy as a socially conditioned and therefore unnatural state, and so on – will not be surprised to hear this is a heavily indulgent work. Not without its lively moments, the film is an uneasy blend of a meta-comedy about a ménage-à-trois and a sincere essay film on Cádiz. As such, it keeps itself busy for its two-hour running time, but García Pelayo’s implication-cum-assertion, that the most interesting thing about a city is its women, seems like a perverted joke.

|

| Alegrías de Cádiz / Joys of Cádiz |

|

| 10.000 noches en ninguna parte / 10,000 Nights Nowhere |

|

| Los chicos del puerto / The Kids from the Port |

All the more refreshing, then, to watch more upbeat films like El Rayo, Un ramo de cactus and Las aventuras de Lily ojos de gato. The first of these, directed by Fran Araúgo and Ernesto de Nova, screened in SEFF’s ‘Andalusian Panorama’ section following a world-premiere at San Sebastian, and sees a defiantly high-spirited itinerant labourer trekking across Spain back to Morocco on a tractor. The second, which received its world-premiere at SEFF as part of the festival’s inaugural ‘Resistances’ strand, is a pleasing if sometimes technically amateurish comedy by Pablo Llorca, featuring a deceptively masterful central performance from Seville-born Pedro Casablanc, who has in recent years been ubiquitous on Spanish television. Casablanc’s deadpan style and pockmarked face recall Bill Murray, and his turn in Llorca’s film – as a fiftyish farmer at odds with his family’s acceptingly money-oriented ways – deserves much wider recognition. In contrast to a film like Los chicos del puerto, both Un ramo de cactus and El Rayo demonstrate that a serious film need not be glum.

Las aventuras, meanwhile, is a night-in-the-life-of tale centring heavily on inebriation as a means to forget. Working as a PR for a bar in Madrid, Lily (Ana Adams) meets a bleary-eyed customer with whom, after hours, she solemnly swears to drink till she hits the ground – and perhaps would if real-life events didn’t get in the way. To be sure, Lily is drinking away the hurt of a break-up, but her temporary escape is frustrated by more pressing matters: a friend’s pregnancy, her new pal’s paralytic state, an abusive employer, and so on. A more systemic understanding of things might be beyond Boix and his film; I would have preferred a less cartoonishly cruel boss, for instance. And though these are palpably more universal features with which to pepper a story – as opposed to the characteristics of the Galician landscape, or the political fate of Spain – the film nevertheless has an undeniable strength, in taking an otherwise insufferable young drunk and accounting for her self-destructive behaviour in a non-evasive way. Played by British actress Adams – who speaks Spanish fluently – Lily has a rugged, get-on-with-it edge, which makes her charming even when she’s actively derailing a blues performer’s final song in a late-night bar.

|

| Las aventuras de Lily ojos de gato / The Adventures of Lily Cat Eyes |

Michael Pattison is a freelance film critic based in

Gateshead, UK. He blogs at idFilm and Tweets @m_pattison.