Wednesday, 5 March 2014

Tuesday, 4 March 2014

La plaga / The Plague Year (Neus Ballús, 2013)

I think that La plaga could be looked at in combination with Arraianos because they both use non-actors in a rural setting, and walk a line between documentary and fiction. Documentary is a recurring theme in Caimán’s list.

Monday, 3 March 2014

Sunday, 2 March 2014

Saturday, 1 March 2014

Friday, 28 February 2014

Project 2014

As outlined in my Belated Birthday post, I'm changing focus this year to look at Spanish cinema from a different angle; I'm going to investigate what Caimán Cuadernos de Cine have called 'el otro cine español' and also the increasingly noticeable trend for 'cine low cost'. I'm at the viewing stage of this project at the moment, and expect to be for a while. I'm currently working my way through Intermedio's Pere Portabella boxset, which may seem like going off at a tangent but I actually think that it would be difficult to discuss 'non-mainstream' cinema originating from Spain (and the autonomous communities) without looking at his career, because what's happening now is not completely 'new': there have always been 'other' cinema(s) at play, but perhaps the perception has 'resurfaced' or these films have become more visible in the past 12-18 months (for a variety of reasons to be expanded on at a later date). Of Portabella's 6 features and 16 shorts, I have 2 features and 5 shorts left to watch (which is uncommonly speedy for me): I will write about the set once I've finished it.

At the same time, I've been taking Caimán's list of 52 directors who they think pertain to this 'other' cinema as a jumping off point for my viewing. I have issues with the list (and, again, I'll come back to that at a later date), but it's as good a starting point as any, and has introduced me to some names I didn't know. But I am also looking at directors not on the list, who don't fit Caimán's criteria but who seem to me to be ploughing a similar field. I'm not going to write about every film at the time of viewing, and there are some that I probably won't return to later either, but I want some kind of record of progress on here: I'm going to post a still from each film viewed and tag it 'project 2014' (if it relates to this) [UPDATE (Dec 2014): As the project will be continuing in 2015, I'm going back through the posts to change the tag to just 'project']. Rather than post what I've watched so far all at once, I'm going to schedule an image to be posted each day this coming week. I'm not going to post any of the Portabella ones because I am going to write about them soon. The 'other' cinema and 'cine low cost' overlap but they are not synonymous, so I will probably tag the images with one or the other (or both) of those as well, but I'm starting primarily with the former.

At the same time, I've been taking Caimán's list of 52 directors who they think pertain to this 'other' cinema as a jumping off point for my viewing. I have issues with the list (and, again, I'll come back to that at a later date), but it's as good a starting point as any, and has introduced me to some names I didn't know. But I am also looking at directors not on the list, who don't fit Caimán's criteria but who seem to me to be ploughing a similar field. I'm not going to write about every film at the time of viewing, and there are some that I probably won't return to later either, but I want some kind of record of progress on here: I'm going to post a still from each film viewed and tag it 'project

Monday, 24 February 2014

Saturday, 15 February 2014

Saturday, 8 February 2014

Belated Birthday

|

| My favourite of the Spanish films I've seen in the last twelve months, Atraco a las tres / [Bank Robbery at Three O'Clock] (José María Forqué, 1962) |

An email telling me that the Nobody Knows Anybody twitter account had turned three alerted me to the fact that I had forgotten the blog’s birthday (on Thursday 6th). Caught up in other things, it had passed me by; I have entered the fourth year of this blog’s existence in much the same way as I conducted the third one.

2013 was not a brilliant year for me. There were some positives: I finally managed to get a full-time job, after years of being stuck in part-time employment; I delivered a paper at an academic conference for the first time in more than five years; I started going to the cinema again, after a couple of years of not really bothering (a combination of it being too expensive to be a regular habit and an increasingly ‘meh’ attitude to life in general and recent cinema in particular – La grande bellezza shook me out of the meh-ness (I saw it three times on the big screen), and full-time hours mean that I can now afford to go more often); and people started writing guest posts for the blog (which is exciting for me and something I really appreciate – so, thank you Fiona Noble, Michael Pattison, and Rowena Santos Aquino). But the negatives were at times overwhelming: three weeks after I started the job, the institution I work for announced a full restructure and I (along with all of my colleagues) had to reapply and be re-interviewed for a reduced number of jobs (I hung on to my job, but the process took a couple of months and the aftermath of redundancies and reassignments, and the general feeling that good people have been messed around, was horrible and still lingers six months later); and a member of my immediate family was in hospital for surgery on three separate occasions (the last just before Christmas), which has been stressful and emotionally draining.

So, bring on 2014!

Certain things were also clarified for me. I enjoyed the conference, which surprised me because I’ve not had good experiences with academic conferences in the past (in my experience they seem to attract people who need to make others feel small in order to make themselves feel big –a lot of unnecessary point scoring– but on this occasion everyone was lovely) and having listened to so many people researching one of my main areas of interest (but in a variety of different contexts), I left feeling that my spark of enthusiasm had been reignited. However you’ll note that I said ‘listened to’ rather than ‘spoken to’; I find navigating large groups of people I don’t know to be a bit of an anxiety generator, and it sometimes brings out my shyness to an incapacitating degree. I’m fine in small groups, or one-to-one, but I avoid large gatherings if possible. But I felt I had to go, and that I had to submit a paper, if only to prove to myself that I could and that my brain was still capable of functioning in that way. So I went. But I also know that that probably isn’t the forum I would choose to put myself into again anytime soon. What it also clarified is that I don’t think that ‘academia’ is what I’m aiming for; I want to write about films but not necessarily in that way. That’s not to say that I won’t write something up as an article and submit it to an academic journal if I have an idea that suits that setting, but I’m not setting out for an academic publications profile. The purpose of creating and sustaining a list of (academic) publications is usually to acquire an academic position / footing, and I don’t want to be ‘an academic’. But I also think that there are different (and more immediate) ways to share information, ideas, and arguments about films (from my personal perspective, Mediático and Modern Languages Open are interesting developments in that regard). I realise that whatever form you choose to work or publish in, there are hoops to be gone through, but I find that I am quite picky about which hoops I will choose to jump through. At the same time, some ‘requirements’ don’t seem like hoops at all because they’re part-and-parcel of something you enjoy doing and how you view the world. But I'm more interested in textual analysis than theoretical frameworks, and I'm currently trying to find my voice with that focus.

I have made a start with considering different forms / arenas of publication, but I won’t mention particulars unless / until I have something concrete. That said, I have ‘signed up’ (and am looking forward) to contributing to Mediático (initial topic still to be decided), a new blog focussing on Latin American, Latino/a, and Iberian media and film studies (find them on twitter @MediaticoMFM). In terms of what I write about, I’ve come to a number of conclusions in the past year: the blog is really helpful for working through ideas because I think by writing, and something larger can be approached piecemeal and without pressure to be ’perfect’, and it can be returned to as and when I'm ready, so that over time I can hone my thinking and can see the shape that the argument or discussion needs to take (a case in point is the Javier Bardem ‘issue’ I kept returning to, which has now turned into something else entirely and which I have submitted for consideration at an online (open access) journal); I should draw a line under some of the topics that were the basis of my PhD and look at other things; I need to be more focussed because the ‘random viewing’ thread, although it does reflect my viewing habits most of the time, does not allow me to be consistent or coherent in thinking things through; I don’t need to write about every Spanish film I watch (this relates to the previous point, but sometimes I just don’t have anything to say about a particular film and at that point I should just move on); in order to improve and expand my writing, I should write about cinema more broadly (i.e. not just that which originates from Spain).

So, the blog will continue but with a few changes. One element of my PhD research that I haven’t done much with is the industrial component, which I think is currently an interesting topic because the Spanish film industry has been generally imploding for at least the past 12-18 months. An offshoot of that has been the development of what is being referred to (by Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, at least) as ‘El otro cine español’ and the general trend for ‘cine low cost’ and initiatives and / or platforms such as #littlesecretfilm and Márgenes. I’m intending to mainly focus on these topics (and how they interrelate; not everyone thinks that the low cost development is good for the future of cinema made in Spain) for the next year, initially by watching a lot of films and getting a sense of what this ‘movement’ (if that is what it is) comprises and what it doesn’t; I will be looking for connections but will probably write about the films individually, or by director, to begin with. But from now on I won’t be writing about every film viewed. I’ll probably post a full list at the end of the year or something like that instead. My Carlos Saura Challenge will restart, hopefully soon, but I’m not going to attempt to give a timetable because I always break from it (but my aim has to be for more than another 6 films in the next twelve months, otherwise it'll take me more than six years to work my way through his filmography). I hope that there will be more guest posts – please tweet me or comment below if you have an idea for a post. It can relate to any aspect of Spanish cinema; starting a dialogue with people was one of my original intentions with the blog. Which brings me to my last point: writing about cinema outside of Spain. I’m not entirely sure what I’m going to do or how I’m going to do it. In relation to Spanish-language cinema (that isn’t technically 'Spanish’), I may still just post that here (as I did with my Pablo Larraín post), but I have also got a couple of ideas for things that in no way relate to this blog, so I will have to have a think about that. If I argue (as I do) that the emergence of specific actors / stars doesn't happen in a vacuum, that there is an industrial as well as a cultural context to their creation, the same is also true of Spanish cinema(s) more broadly; 'it' (cinema in Spain is not singular) exists within a wider network of events and circumstances and my trips to the cinema in the second half of 2013 highlighted for me that I need to pay attention to that wider context as well. So something non-Spanish should start appearing at some point in 2014 (later in the year, if I’m being realistic).

Ordinarily by this point in the year I have posted ‘my top 5 of [previous year]’ and ’10 films to look out for in [the current year]’ posts. I’ve decided not to do that this year. My top 5 post would relate to Spanish films from 2013 and 2012 (because I mainly see things on DVD the year after their Spanish release) but I didn’t see enough films from those years in the last twelve months (I saw five, so it would be like just putting them in order of preference rather than actual favourites, and there were at least two of them that I didn’t rate) – between Carlos Saura and Alfredo Landa, I watched a lot of older films last year. In terms of the films coming this year, a couple of the ones I highlighted last year have still yet to be released (generally due to funding falling through) and at least one has stalled in pre-production (the Saura one, obviously), so there didn’t seem much point in attempting another full-blown list. Of the ones outstanding from last year, I am still interested in: Murieron por encima de sus posibilidades (dir. Isaki Lacuesta) and Presentimientos (dir. Santiago Tabernero) (the latter has been released in Spain in the past week or so). Of films that are ‘finished’ or well into production (as far as I can tell) and due for release in 2014, I will keep an eye out for: Magical Girl (dir. Carlos Vermut); La novia (dir. Paula Ortiz); Carmina y amén (dir. Paco León); La isla mínima (dir. Alberto Rodríguez); and El niño (dir. Daniel Monzón).

Labels:

2013,

2014,

Anniversary,

plans

Thursday, 23 January 2014

Guest Post: Rowena Santos Aquino - Liminal Worlds and (Levinasian) Encounters in The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and The Orphanage (2007)

Guillermo del Toro and Contemporary Spanish Cinema

Guillermo del Toro has stated many times that The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) are brother-sister companions. These two films constitute del Toro’s only Mexican-Spanish co-productions, with children as the main protagonists and set in Spain (at the end of the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s and in Franco-fascist Spain of the 1940s, respectively). With their imaginative narratives, political undertones, and technical innovations, these two films have been the subject of numerous essays and articles that tease out how they function simultaneously as repressed historical memories, fairy tales, gothic stories, and variations of the horror genre.But another pairing between one of del Toro’s above-mentioned films and a Spanish film produced by del Toro can also tease out themes of trauma, how secrets of the past impact the present, childhood and/in violence, and social rites of passage in an interesting way: The Devil’s Backbone and Juan Antonio Bayona’s debut feature The Orphanage. In these two films, the intimate connection between play and violence amongst children, or put another way, the fine line that separates play and violence, is the seed from which such themes develop.

The Devil’s Backbone is set at the tail end of the Spanish Civil War, in an orphanage in the middle of the remote Spanish countryside. It deals with a boy named Carlos (Fernando Tielve), his experiences of being left at the orphanage, and his gradual discovery of the history that the place has witnessed in the midst of the war. This history involves the death of Santi, one of the orphans, another of the orphans’ possible involvement in his death, and Santi’s ghost wandering at the orphanage amongst the boys. The Orphanage, produced in part by del Toro, tells of married couple Carlos (Fernando Cayo) and Laura (Belén Rueda) and their adopted son Simón (Roger Príncep) moving into what once had been the orphanage where Laura had lived before being adopted herself. Simón disappears without a trace and Laura suspects a phantasmal hand behind his disappearance. A former caretaker at the orphanage then appears at Laura’s doorstep, which leads her to confront the orphanage’s past of the deaths of several children and its possible relation to her son’s disappearance.

The Liminal and the Ritual

The delicate transition from (childhood) play to violence and its consequences shapes the kind of worlds that The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage present, the kind of characters that populate them, and the series of events that occur to the characters. The traumatic consequences of this transition are the deaths of children, in the large-scale context of war and the small-scale context of a family, respectively. Each film is about unearthing the past that lead to such deaths. Inversely, each film is about scrutinising the present that maintains this past a secret and known only to the very few. The ghostly element comes in to visualise the traumatic pasts in question and their ongoing resonance in the present. Yet the child ghosts that are such an important element in both of these films do not serve to scare or shock. Rather, they reflect back, or recall, to the world of the living the actual horror that lies in humans, young and old, regarding war or discrimination.

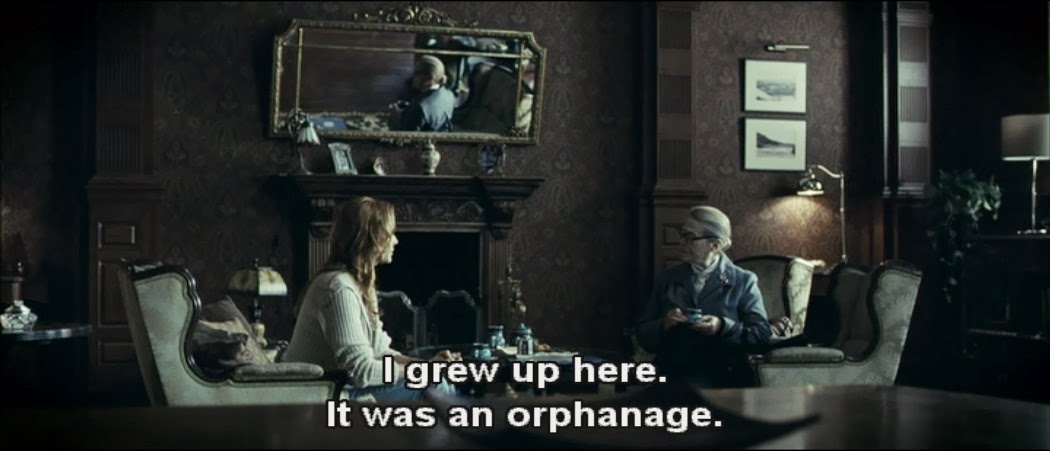

Both of these films’ worlds are therefore marked by liminality, or the in-betweenness marking the before and after of change: between childhood and adulthood (age), play and violence (social), past and present (temporal), hidden and known (status), ghost and flesh (corporeal). Significantly, ‘liminality’ in anthropological terms is the intermediate stage of a rite of passage. The child ghosts in these two films have adult counterparts that embody this quality. These adult counterparts have a personal association with the orphanage that positions them in that liminal space between childhood and adulthood. In The Devil’s Backbone, that link is Jacinto (Eduardo Noriega), who spent fifteen years of his life at the orphanage (Figures 1-2). Though he hated his time at the orphanage and wants no one from the outside world to find out that he had lived there, he has returned to work at the site as the groundskeeper to steal the gold hidden at the orphanage. The kind of man that he has become (a distillation of a fascist, stopping at nothing to get what he thinks is due him, from children and adults, men and women, alike) is related directly to his childhood experiences of abandonment. In The Orphanage, that link is Laura, who was once a resident at the orphanage that she and her husband have now made their home (Figures 3-4). Unlike Jacinto, Laura is more at peace with her (brief) time spent at the orphanage: she and her husband have not only bought the former orphanage as their home, but they also want to use part of it to house and care for disabled children. The kind of experiences that she suffers in the film (her son’s disappearance and presence of ghosts in the home) is related directly to her childhood friendships at the orphanage. Both of these adults at the films’ conclusions enact a reverse rite of passage that brings them back to their childhood, though under differing circumstances and degrees.

|

| Figure 1 |

|

| Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 3 |

|

| Figure 4 |

The Gothic and the Fairy Tale

The liminal state in a rite of passage is often marked by physical isolation, even invisibility, in relation to society. This element of isolation and invisibility from society is perhaps most expressed in the Australian Aboriginal ritual of the walkabout, a journey through the wilderness undertaken by a male adolescent. The walkabout can last up to half a year, after which the adolescent returns to society as a changed person. The element of isolation and invisibility in The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage manifests itself in both films through a singular setting: an orphanage, in the middle of the countryside and by the seaside, respectively (Figures 5-6).

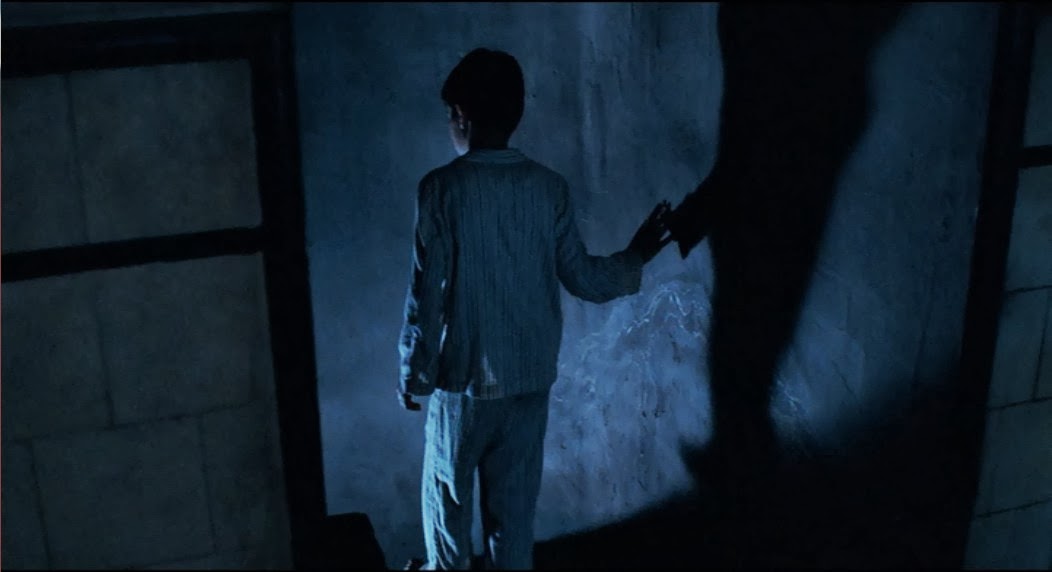

In The Devil’s Backbone, after Carlos is left at the orphanage with no explanation, his entry into its world involves multiple initiation rites that thrust him (and his new friends) into premature adulthood. During his first night at the orphanage, his brief encounters with Santi’s ghost and his entry down in the cellar where Santi’s ghost mainly resides act as initiation rites to be accepted by the other boys. Later in the film, his place among the boys fully accepted and the hidden past of Santi’s death revealed by one of them, Jaime (Íñigo Garces), together they transform the cellar into a place of collective struggle against the fascistic Jacinto. In The Orphanage, in his own way Simón also undergoes a rite of passage. In fact, his rite of passage is a lot more accelerated than Carlos. Through the ghosts of Tomás and of Laura’s childhood friends (who are never seen on screen), Simón learns very quickly of his adopted status and his mortality, secrets that Laura and her husband were keeping from him.

Significantly, the singular setting in both films is also a mark of gothic fiction, as the container of a secret, sometimes a treasure, and the site of violence and traumatic past that gives birth to the secret and the narrative drive to unearth it. More specifically, in gothic fiction, underground structures such as cellars, catacombs, caves, and the like have particular resonance. Architecturally and spatially, these underground structures bring together the plot points of secrets, treasure(s), unknown traumatic pasts, and even ghosts. Both The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage are marked not only by their sole isolated settings, but also variations of subterranean spaces. In The Devil’s Backbone, it is the cooking area with a hearth, which is not only where the safe storing the gold is hidden but also the entryway to the cavernous cellar where Santi’s ghost dwells (Figures 7-8). This cavernous cellar was, in fact, the site of Santi’s death. In The Orphanage, it is the house’s outdoor shed where Laura sees the one who killed her childhood friends at the orphanage without knowing it early in the film. But it is also the cave by the seaside where Simón first meets the ghost of Tomás, whom Laura gradually learns was a deformed boy whose mother Benigna (Montserrat Carulla) worked at the orphanage and had hidden him from her colleagues (Figures 9-11). While playing with Laura’s friends, who were hounding him to take off the paper bag that served as his mask, Tomás died. Lastly, it is also the house’s basement, whose secret entryway is a door inside a closet and where Laura eventually finds not only her son but also Tomás’ past (Figures 12-13).

|

| Figure 5 |

|

| Figure 6 |

Significantly, the singular setting in both films is also a mark of gothic fiction, as the container of a secret, sometimes a treasure, and the site of violence and traumatic past that gives birth to the secret and the narrative drive to unearth it. More specifically, in gothic fiction, underground structures such as cellars, catacombs, caves, and the like have particular resonance. Architecturally and spatially, these underground structures bring together the plot points of secrets, treasure(s), unknown traumatic pasts, and even ghosts. Both The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage are marked not only by their sole isolated settings, but also variations of subterranean spaces. In The Devil’s Backbone, it is the cooking area with a hearth, which is not only where the safe storing the gold is hidden but also the entryway to the cavernous cellar where Santi’s ghost dwells (Figures 7-8). This cavernous cellar was, in fact, the site of Santi’s death. In The Orphanage, it is the house’s outdoor shed where Laura sees the one who killed her childhood friends at the orphanage without knowing it early in the film. But it is also the cave by the seaside where Simón first meets the ghost of Tomás, whom Laura gradually learns was a deformed boy whose mother Benigna (Montserrat Carulla) worked at the orphanage and had hidden him from her colleagues (Figures 9-11). While playing with Laura’s friends, who were hounding him to take off the paper bag that served as his mask, Tomás died. Lastly, it is also the house’s basement, whose secret entryway is a door inside a closet and where Laura eventually finds not only her son but also Tomás’ past (Figures 12-13).

|

| Figure 7 |

|

| Figure 8 |

|

| Figure 9 |

|

| Figure 10 |

|

| Figure 11 |

|

| Figure 12 |

|

| Figure 13 |

Tempering both of these films’ gothic fiction elements is their fairy tale aspect. Children at the center of the narratives constitutes but one manifestation of this fairy tale aspect. Related to children protagonists is the thematic of abandonment, encapsulated by the very purpose of an orphanage, where Carlos ends up in The Devil’s Backbone and where Laura and Simón remain, despite their adopted family ties. The singular, far-flung setting of the orphanage in both films echoes this theme of abandonment. Another manifestation of the fairy tale aspect comes in the form of objects. In particular, keys in both a literal and figurative sense of enabling the crossing of thresholds are prominent in the two films (Figures 14-17). The notion of crossing thresholds links back to the liminality of these microcosms, between past and present, ghost and human, child and adult, play and violence. Thus, keys denote not just keys or door knobs to open doors or safes but also old photographs to access the past. In The Devil’s Backbone, connecting these literal and figurative keys is Jacinto. He surreptitiously steals the keys from Carmen (Marisa Paredes), the orphanage’s head administrator and teacher, one at a time to find the one that would unlock the safe containing the gold. He also has the keys to the cooking area whose cellar is the site of Santi’s death. And towards the film’s conclusion, he discovers the old photographs of himself as a baby and boy, with his parents, constituting a rare moment of introspection on his part. This moment is a pause in his role as the fairy tale ogre who towers above the children and menaces them because he knows no other way to express himself. At the end of the film in his final confrontation with Carlos and the other boys, the film compares him to the extinct woolly mammoth, about which the boys learn in a lesson with Carmen in the middle of the film. In The Orphanage, connecting the literal and figurative keys is Simón. Following his encounter with the ghost of Tomás in the cave, he performs a very fairy tale-esque gesture of leaving a trail of shells from the cave to his house for Tomás to follow; in this way, the shells serve as a variation of a key to access a space (Figures 18-19). Subsequently, a game of pursuing object-related clues (or keys) begins at the house, which leads Simón to unlock literally and figuratively the knowledge of his adoption and illness. When he disappears, he becomes a kind of key himself for Laura to access the secret past involving Tomás, his death, and those of Laura’s friends at the orphanage.

|

| Figure 14 |

|

| Figure 15 |

|

| Figure 16 |

|

| Figure 17 |

|

| Figure 18 |

|

| Figure 19 |

Definitions of a Ghost

As mentioned earlier, more than anything, the child ghosts in The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage reflect back, or recall, to the world of the living the actual horror that lies in humans, as opposed to serving as mere scare or shock tactics. We return to the thematic realm of the liminal and the ritual, of childhood and adulthood, ghosts and bodies, play and violence. Santi’s ghost in The Devil’s Backbone and the ghosts of Tomás and Laura’s childhood friends in The Orphanage are products of human actions instead of something fantastical. At the same time, these films are careful to avoid demonising the human element that ends up being much more horrific than the ghosts: Jacinto and to a lesser extent Jaime in The Devil’s Backbone and Tomás’ mother Benigna and to a lesser extent Laura’s childhood friends.

Through the vehicle of ghosts, these two films enact encounters with the traumatic, the horrific, the flawed, and the unknown, in other words, for Carlos in The Devil’s Backbone and Laura in The Orphanage. These encounters with the more melancholy and unsettling, darker, and uglier facets of life constitute rites of passage in their own way. When initially confronted by the notion of ghosts, both Carlos and Laura recoil from or deny them, based on their seeming incomprehensibility. In doing so, they recoil from or deny the actual pasts, marginalised and hidden, to which they refer. Yet in the course of the films, both Carlos and Laura, among others, learn to face what they do not know or understand. This process of facing the incomprehensible and therefore fearful is made literal with the ghosts in both films. Taken further, in the context of the ritualistic, liminal, and confrontational, The Devil’s Backbone and The Orphanage’s encounters with ghosts chart the process of not only facing the incomprehensible and fearful but also realising one’s connection to it, on a humanistic level.

Both films ponder definitions of the ghost: The Devil’s Backbone in its prologue and The Orphanage midway through the narrative. Both films ask, plainly, ‘What is a ghost?’ In so doing and through their definitions, they emphasise the characters’ encounters with the ghosts as something beyond the function of scaring audiences and towards something like ethical action and responsibility, in keeping with the idea of one’s connection to the incomprehensible and fearful, on a humanistic level:

The Devil’s Backbone: ‘A tragedy doomed to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain, perhaps. Something dead which still seems to be alive. An emotion, suspended in time. Like a blurred photograph.’

The Orphanage: ‘When something terrible happens, sometimes it leaves a trace, a wound that acts as a knot between two time lines. It’s like an echo repeated over and over, waiting to be heard. Like a scar or a pinch that begs for a caress to relieve it.'

Each film’s definition of a ghost shares characteristics with the other: repetition; something between living and dead, or past and present; and a physical pain with an indexical counterpart that is not always seen but asking to be acknowledged. In their philosophical definitions of a ghost, these two films locate themselves in a nearly Levinasian realm of face-to-face encounter, echoed literally by Carlos’ meeting Santi’s ghost in The Devil’s Backbone (Figures 20-22) and more figuratively by Laura playing along with the ghosts of Tomás and her childhood friends (Figure 23).

|

| Figure 20 |

|

| Figure 21 |

|

| Figure 22 |

|

| Figure 23 |

In his 1984 essay ‘Ethics as First Philosophy,’ Levinas writes,

‘A responsibility that goes beyond what I may or may not have done to

the Other or whatever acts I may or may not have committed, as if I were devoted

to the other man before being devoted to myself. Or more exactly, as if I had to

answer for the other’s death even before being. A guiltless responsibility,

whereby I am none the less open to an accusation of which no alibi, spatial or

temporal, could clear me. It is as if the other established a relationship or a

relationship were established whose whole intensity consists in not presupposing

the idea of community. A responsibility stemming from a time before my

freedom – before my (moi) beginning, before any present. A fraternity existing

in extreme separation. Before, but in what past? Not in the time preceding the

present, in which I might have contracted any commitments’ (83-84, The

Levinas Reader, ed. Seán Hand, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005).

Strikingly, in his audio commentary to the 2013 Criterion DVD of The Devil’s Backbone, del Toro states along similar lines about the gothic romance, which can also apply The Orphanage:

‘It’s the only genre that teaches us to understand the otherness. At its best,

it is probably the most humanistic genre there is, because by being fascinated

by [and] by being sort of in love with the monsters, we are exercising, in the

abstract, the most beautiful form of tolerance: a desire to understand the

other […], as opposed to trying to destroy it and wipe it from the face of the

earth.’

Rowena Santos Aquino is a Lecturer in the Department of Film and Electronic Arts at California State University, Long Beach. You can find her on twitter, @FilmStillLives.