|

| Patricia Heras |

This post is more about the case that Ciutat Morta takes as its focus than about the film itself - it may be easier to revisit the documentary as a film at some point in the future when the case has stopped whirling around in my head. But after writing last year about the censorship or suppression of documentaries in Spain in relation to Rocío (Fernando Ruiz Vergara, 1980) and Edificio España (Víctor Moreno, 2013), I find myself returning to the theme in 2015, following the censored broadcast of Ciutat Morta on Catalan TV this past weekend. I didn't initially find anything written in English about the case (the censorship or the event the film is about) - but the story has appeared on The Guardian's website today. In essence, Ciutat Morta details what appears to be a gross miscarriage of justice - in fact justice has little to do with the matter - wherein a group of young people were brutalised and tortured by the police, the latter ably supported by the Barcelona judicial and political classes, and prosecuted for a crime to which there is no physical, forensic, or independent eye-witness evidence of their involvement. Corruption, collusion, and self-interest combined in a poisonous brew alongside racism, xenophobia, and homophobia in what is suggested to be a systemic pattern of behaviour within official bodies in the city.

On the night of 4th February 2006 on the Calle de Sant Pere Més Baix in Barcelona, a Guàrdia Urbana (urban police) operation sought to evict a party (of several hundred people) from an occupied theatre. As the police approached the theatre, one agent (not wearing a helmet) was hit on the head by an object and grievously injured (he would go into a coma). Those are the only uncontested facts of the incident. Early reports (repeated by Barcelona's then-Mayor, Joan Clos, in a radio interview) suggested that the agent was hit by a plant pot that either fell or was thrown from the roof of the theatre - and video footage from that night clearly shows those on the ground shouting that things are being thrown from above and urging other officers to put helmets on. However nobody from inside the theatre was arrested. Instead the police led a baton charge against those in the street (i.e. people who could not have thrown anything from the roof) and arrested seven people - three Latin American young men (Rodrigo Lanza and Álex Cisternas from Chile, and Juan Pintos from Argentina - each of whom has either Spanish or Italian nationality), a German girl, and three Catalans (the latter four are not named within the documentary, so my assumption (which may be wrong) is that they were released fairly quickly in comparison to the other three). Two more people (Patricia Heras (who was from Madrid and had only moved to Barcelona six months earlier) and Alfredo Pestana) would be arrested later in the night after having the misfortune to cross paths with the police at the hospital where the latter had escorted the Latin Americans for treatment after an initial beating at the police station following their arrest. Xavier Artigas and Xapo Ortega's documentary tries to unpick the series of events that followed, a tangled web of violence and torture, combined with police, judicial and political obstruction.

It may be best to start with an outline of the basic facts:

- After being arrested at the hospital, Patricia and Alfredo were put at the disposition of the Mossos d'Esquadra along with the five who had been arrested in Calle de Sant Pere Més Baix.

- Amnesty International supports the official complaint by Rodrigo, Juan, and Álex that what happened next (quite aside from the earlier brutality they had suffered) was that they were tortured by masked officers who concealed their ID numbers. Amnesty included the complaint in their 2007 report given to Barcelona City Council - their concern was that complaints against the Mossos were not being investigated.

- The first judge the defendants encountered - Carmen García Martínez - ignored the evidence of torture.

- All nine of the people arrested had European passports, but only the Latin Americans were kept in custody while awaiting trial. They were in prison for two years before the trial started, the maximum amount of time that an accused person can be held before being tried under the Spanish State.

- The trial began in 2008. Spain has an 'investigating magistrate'-style legal system (by my understanding that role was taken by Carmen García Martínez) and jury trials seem to be quite rare - this case was heard by the Audiencia Provincial de Barcelona (effectively a panel of magistrates).

- The police changed their version of events to fit the location of the people arrested in the street - saying that the injured officer was hit by a stone thrown from street level. The forensics / medical experts said that this was incompatible with the injuries suffered by the officer - the kind of fracture he sustained could only have been caused by a large heavy object coming from above.

- If the object came from the roof and no culprit could be found - and it would be impossible to identify who threw it given the number of people on the premises that night - civil liability would be down to the owner of the building. The building in question is owned by Barcelona City Council.

- No physical evidence (plant pots or stones) was collected from the street on the night of 4th February because Barcelona's clean-up team swept up before the forensic investigation could begin. It has never been ascertained who gave the order for the clean-up crew to clear the street.

- A lot of evidence requested by the defence (specifically the opportunity to question officials who may have had access to different pieces of information relating to the chain of command and control of information) was denied.

- The defendants were convicted on the basis of police testimony alone. No physical, forensic, or independent eye-witness evidence supported the version of events put forth by the police.

- At each stage of the investigation and subsequent trial, the various arms of the State (police, judiciary, local politicians) backed each other up despite evidence pointing to the innocence (and severe mistreatment) of the defendants.

Rodrigo, Juan, Álex, Patricia, and Alfredo were all found guilty (despite ambulance drivers placing the latter two elsewhere in the city at the time of the incident) and given sentences ranging between 2.5 to 4.5 years (lenient given the severity of what they had been accused of). Time already served meant that Rodrigo, Juan, and Álex were released on parole. All five appealed their sentences, only for them to be upheld and the sentences lengthened, meaning that in 2010 the Latin Americans were returned to prison for an additional two years and Patricia was also jailed in October of that year (Alfredo was pardoned before entering prison). In December 2010, Patricia was put into a semi-open work release programme but was unable to settle into a routine (or, as one friend explains, to accept a social punishment she had not earned) and fell into a depression. She committed suicide on 26th April 2011 while on day release. Rodrigo was the last of the defendants to be released from prison, in December 2012.

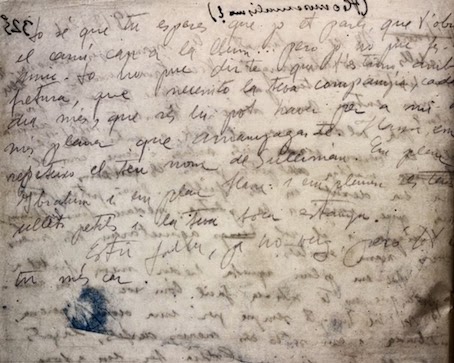

Given the amount of exposition required to explain all of this, and also taking the time to consider legal, personal, and sociological angles on the issues raised, a lot of talking head footage is utilised by the directors. However the film never loses sight of the human cost paid by the defendants and their loved ones, and they manage to avoid a dull back and forth (it would admittedly be difficult to make this story dull, but it could still have become a dry retelling), instead composing a complex but coherent overview of a case that has been deliberately obfuscated by powerful vested interests. One particularly effective device is a clock superimposed over the screen, showing a minute ticking by. This first appears after Rodrigo gives an account of the initial beating received at the police station (which left behind a pool of blood bigger than himself, a visual image that clearly made an impression on him because he repeats the phrase several times with the same confusion he says he felt at the time (i.e. how could the pool of blood be bigger than him?)) – he says that maybe it only lasted a minute, but it felt like eternity. The clock then ticks down a minute in silence, not just indicating the time passing but also the isolation of being completely on your own in those circumstances. The device recurs later on superimposed over footage of one of the policemen named in the official complaint working out at the gym; as the man sets about kicking and punching a full-size punch bag, barely breaking a sweat, you appreciate how much damage he could do to a human being in the same amount of time. But the heart of the film is the absent Patricia. The film fleetingly resurrects traces of her through a combination of still images and the memories of those who knew her, and she is given a voice via her poetry (read as voiceover by her former girlfriend, Silvia Villullas), but her absence is palpable nonetheless.

It was Patricia's suicide that brought the case to the attention of Xapo Ortega (an architect) and Xavier Artigas (a sociologist) - two men who had not long met via the audiovisual commission relating to 15-M and were looking to work on local stories together. Patricia became the focal point for the protests relating to the case (known as 4-F, or #4F on twitter). As Gregorio Morán, a journalist at La Vanguardia who wrote about Patricia at the time (here and here [the latter has been translated into English]: he is one of the few local journalists to have covered the case - silence was the norm), the young woman stands out because of her sensitivity and the articulacy of her self-expression in the poetry and diaries she left behind (her personal blog - The Dead Poet - is still online, including her first person account of her arrest and subsequent treatment). She was essentially arrested because she was 'different' and her belonging to a marginal social group was manifested in her appearance (the specific thing seized on by the police was that part of her head was shaved in a chessboard pattern - she was a Cyndi Lauper fan). Rodrigo and Juan both highlight that the police statements referred to them as a type via their appearance (they labelled them 'okupa' [squatter] or 'anti-sistema' on the basis of how they were dressed) - the inference being that it was therefore fine to treat them like scum to be washed from the streets (the film gives examples of how such groups are routinely written about in the local press). But as Silvia Villullas points out, the police misread Patricia's appearance in thinking her a punk / okupa - she was actually a goth and more glamorous in how she dressed than the 'label' they put on her. Because they didn't understand her, she was 'other' and therefore not treated as a citizen.

As Ortega and Artigas's investigations got underway several other incidents coalesced to reveal previously hidden information. You could say that these other incidents were unrelated to 4-F except that they reveal that the behaviour of the authorities in that case was not a one-off, and in fact something more widespread and insidious was transpiring. The first piece of information was the likely identity of the author of the initial incident report (mentioned by the Mayor in a radio interview the following day) which referred to a plant pot being thrown from the roof - this report would later be denied as the narrative changed to the stone thrown at street level. Video footage relating to a drug investigation was leaked to the press in December 2009 - one of the videos shows the Guàrdia Urbana's Information Officer, Víctor Gibanel, explaining that he is responsible for the reports and risk assessments of operations that make their way to the Mayor. In the video he is accused by the investigating judge of lying, spreading false rumours, and trying to discredit this very judge - on the basis of the evidence accrued by the judge, Gibanel tells the judge that he will resign. Jesús Rodríguez, a journalist at La Directa, reveals within Ciutat Morta that out of all of the videos leaked in relation to the drug case, this was the only one not to have been made public by the press. Gibanel did not resign, or get fired, and was later promoted by the Mayor.

The version of Ciutat Morta broadcast for the first time on Catalan TV last Saturday night was missing the five minutes relating to Víctor Gibanel - a judge decreed that the documentary infringed Gibanel's 'right to honour' and personal privacy and ordered that the section be censored before broadcast (Gibanel is also suing Jesús Rodríguez for violating his honour, seeking damages of 45,000€). Apparently there was no announcement before the film - or indication within it - to inform viewers that it had been censored (an omission that recalls what happened in the Rocío case). Ciutat Morta has already screened at dozens of film festivals and also in Spanish cinemas (and has been available on Filmin for around a month - although that version has now also been cut) - Gibanel did not protest until the film was due to be broadcast on television in Catalonia (a broadcast that the television channel had been dragging its heels over for several months). His legal actions probably ensured a wider audience for the film than it might otherwise have had - certainly it has made his name better known - and Catalan / Spanish people on social media were (and still are) extremely vocal in highlighting the censorship (as a result it is fairly easy to find the excised five minutes online).

The second incident was the arrest and prosecution of two police officers for the torture of another youth, as well as perjury and falsifying evidence - no Spanish or Catalan news channel reported on the overlap in accusations. Six months after Patricia's suicide, two Guàrdia Urbanas (Víctor Bayona and Bakari Samyang) were sentenced to two years and three months for seriously torturing a young man (known as Yuri J) from Trinidad and Tobago after he attempted to defend a female friend who was being sexually harassed by the off-duty officers. He was tortured in a police station for at least 3-4 hours. To justify the arrest, the officers declared Yuri a drug dealer, but they had finally picked on the wrong person: Yuri was the son of a diplomat who had enough clout to see charges brought against the two officers who could be identified. The two men are mentioned in Patricia's accounts of physical and psychological abuse, as well as named within the official complaint made by Rodrigo, Juan, and Álex - the complaint ignored by judge Carmen García Martínez. Taking the 4-F case in conjunction with the Yuri J one reveals a system beset by racism, xenophobia (Rodrigo, Juan, and Álex were berated within racial slurs during their beatings and were treated differently to the other defendants in terms of not being granted bail), and homophobia (in relation to Patricia).

You would think that the overlaps between the accusations of torture would be sufficient to see the 4-F case reopened (in addition, Ciutat Morta reveals that the authorities are aware of an anonymous witness who has named the person who threw the plant pot, but the latter won't come forward to make an official declaration). You would think. But that had not happened during the film's production and although noise has been growing since the broadcast at the weekend, at the time of writing the prosecution services are saying that the case will not be reopened without new evidence. (Anyone who is interested could probably keep up to speed by searching for #ciutatmorta or #4F on twitter).

The subtitled trailer for Ciutat Morta is here. The film is currently on the TV station's catch up service but if, like me, you don't speak Catalan, you might want to watch it here - with full English subtitles and uncut (for the time being). I've taken that to be a legitimate viewing platform because the film has been uploaded by one of the directors. There is also a link there to buy the DVD although they don't currently have the subtitled version available (I've asked). The interview Fotogramas has posted today with Xapo Ortega and Xavier Artigas may also be of interest.